Article by Art Joyce originally published in the Kaslo Claim by The Valley Voice.

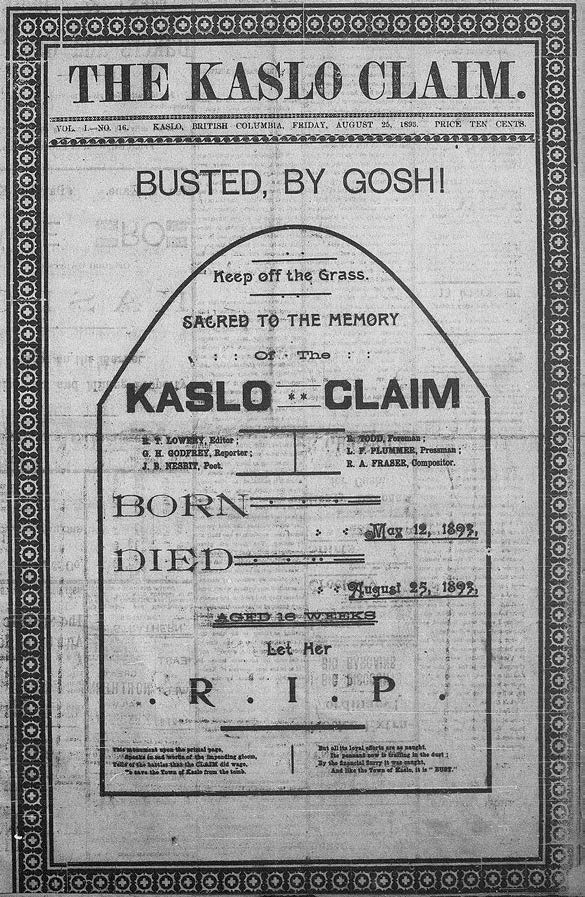

Cover image caption: Colonel R. T. Lowery published the Kaslo Claim in the spring and summer of 1893. It was his first Kootenay newspaper and lasted for 16 editions before closing in August. All advertisers whos accounts were in arrears had their ads printed upside-down. After closing down The Claim, Lowery moved to Nakusp and then New Denver with The Ledge.

Close on the heels of the prospectors and mining speculators that settled the West Kootenay came an equally intrepid breed – frontier journalists. Although the working conditions were marginally better than being stuck down a mine, you had to be tough. Late 19th century journalists and newspaper publishers – they were often one and the same – had to pack heavy letterpresses on horseback from camp to camp when the latest boom went bust, as Nelson Tribune founder John Houston and ‘Colonel’ Robert Thornton Lowery both did. And that often meant trudging along a rough, mountainous trail in backcountry that had yet to see a proper road or a railway. Most importantly, these early Kootenay newspapers engaged in what historian Cole Harris has called ‘boosterism,’ acting as promotional vehicles for the newly established towns.

Kaslo, being the West Kootenay’s earliest incorporated city, was early out of the gate with newspapers too. Its first newspaper, the Kaslo-Slocan Examiner, was established by editor Mark Musgrove in October 1892. It didn’t last long, packing it in by October the next year. Most frontier newspapers sprang up like dandelions and then folded just as quickly, as their owners were forced by economic necessity to move on. Lowery published his first edition of the Kaslo Claim on May 12, 1893. “During the spring and early summer months of 1893, Kaslo remained the mining centre of the Kootenays and gradually took on more frills of civilization,” writes George McCuaig in Kaslo—The First 100 Years. “Saloons of low and high degree lined the streets. There were 14 barbershops where the ‘tonsorial artists’ plied their trade. A bank had been opened…” As Harris has written, “to establish a townsite and erect a few buildings was, in effect, to attract a newspaper.”

Sensing an opportunity for himself, Lowery was anxious to promote Kaslo and district in his newspaper. Lowery was a character of near-mythical stature who loved cigars, poker and whiskey. His ‘colonel’ title was a fiction based on his commanding persona. At only five feet tall, he was a man of small stature, but with an outsized voice, both in person and in print. In his editorial cartoons Lowery threatened to have his office bulldog devour unpaid subscribers. And like his fellow journalists Houston and David Carley (of the Nelson Economist), he shared the prejudices of the day. All of them wrote diatribes against the ‘yellow peril’ of Chinese workers and tended to support exclusionary immigration policies.

But Lowery was a gifted wordsmith, going far beyond merely reporting the facts to give us lucid sketches of life in BC’s 19th century hinterland. In the October 26, 1893 edition of the Nakusp Ledge, Lowery wrote with his usual biting wit of a trek he made on foot from Nakusp to Kaslo. “In some places where the ‘tote’ road resembles an inland sea, we noticed that the trees had been blackened and scorched. This we learned was caused by a profusion of cuss-words striking them so often during the day. We noticed several hats along the road and suppose the owners had been drowned in the mud.”

Often the lifetime of a Kootenay newspaper in the 1890s could be measured in mere weeks. Lowery was forced to shut down the Kaslo Claim after just 15 weeks, running a full-page ad announcing its closure on August 25, 1893. A collapse in silver prices had suddenly taken the steam out of the region’s mining boom. “Busted, by gosh!” read Lowery’s ad, shaped like a tombstone and listing its impressively large staff of six. In the July 28, 1893 issue of the Claim Lowery had paid tribute to an even shorter-lived newspaper, the Lardo Reporter, which had only been established eight weeks earlier. “It is a measure of the role of newspapers in the early years of a mining rush that a case could be made for a newspaper in a place with four houses and two tents,” Lowery wrote, referring to Lardeau.

Then as now, earning a living in journalism was sketchy at best. Although Lowery found it a “pleasant pastime publishing a paper in a primeval forest,” he noted somewhat bitterly that “the men engaged in the publication of a newspaper work harder and get less for it than those in any other calling or business.” After the closure of the Kaslo Claim, he moved to Nakusp, briefly publishing the Nakusp Ledge before relocating the Ledge to New Denver in December 1894. He stayed there until 1904, when he moved to Nelson, disillusioned and broke. Of the 18 newspapers published in the Kaslo-Slocan mining region in the 1890s, Lowery had published four of them, including the Slocan Drill and the Sandon Paystreak.

Kaslo during its 125-year history has hosted a dozen newspapers, including the boom era newspapers the Kaslo Times (1894), British Columbia News (1897-98), Slocan Sun (1898), and Kaslo Prospector (1898-99). The Kootenaian succeeded the short-lived Kaslo Claim in 1895 to become – in its various incarnations – the longest-lived Kaslo newspaper, lasting until 1969. The New Canadian, published in Kaslo during World War II, was the only Japanese-Canadian newspaper not shut down by the government during the war. The Arrow Lakes News was originally published at Kaslo in 1922–23. More modern newspapers have included the Kaslo Update (1983–85), merging with the Kootenay Review; the North Arm Voice, (1989-99); and another short-lived journal, the Kaslo Prospector (1994–95). Although based in New Denver, the Valley Voice has served Kaslo and north Kootenay Lake since its inception in 1992.