Article by Art Joyce originally published in the Kaslo Claim by The Valley Voice.

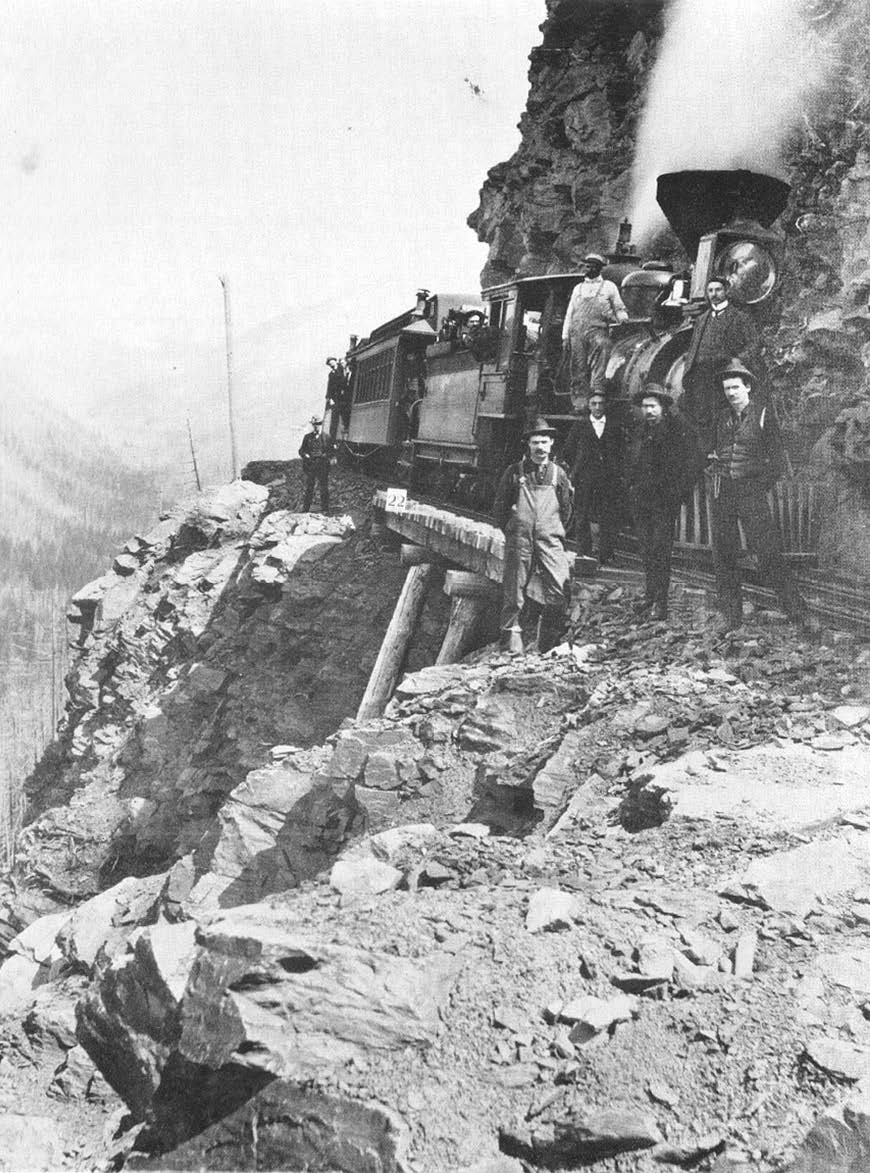

Cover image caption: K&S Railway train beside Kaslo River 23.5 km west of Kaslo. Incorrectly labeled by photographer R. H. Trueman as ‘Carpenter Creek Canyon – K&S Railway near Sandon, BC.’

Anyone who’s a Kootenay history buff has seen it: the classic photo of a locomotive poised a thousand feet above the valley floor at Payne Bluff, taken in 1897 by photographer Richard H. Trueman. The story of the building of the Kaslo & Slocan Railway (K&S) by the Great Northern Railway is one of both accomplishment and disaster. And it’s a reminder that no matter how great our works, Nature remains master.

Picture the scene: a gang of about 20 railroad labourers equipped with nothing but hand tools and dynamite, following the steep grade up Payne mountain, near Sandon. With pickaxes they chop out a path for the crew laying ties and tracks behind them. The narrow gauge track – a three-foot span instead of the four-foot, 8.5-inch span typical of the CPR – is well suited to the precarious terrain. The crew must build more than 30 trestle bridges between Kaslo and Sandon, a monumental task given the rudimentary tools. As a friend of mine said: “People then had to be built of tougher stuff than we are today.”

It’s fitting that Payne Mountain was the scene of this engineering triumph. It was there that Eli Carpenter and Jack Seaton staked the first silver-lead claim in the Slocan mining district on September 9, 1891. The news sparked a massive inrush of prospectors and mining capitalists hoping to get rich – by the next year 750 more claims had been staked. Before the completion of the K&S Railway in 1895, miners had only one way to get the ore down the mountains: by ‘rawhiding.’ Using bundles made of animal hides, miners filled them with ore and then used horses to haul them down the steep trails to ore wagons. You can imagine how dangerous this would be, especially in wintertime. From there wagons would haul them to steamboat landings at Kaslo or Rosebery. You can imagine the miners’ exhaustion after hours and hours on bone-jarring wagon roads. This costly, labour-intensive method was later replaced by aerial tramways at the larger mines, sending ore carts on steel cables down the mountain in a fraction of the time. “Because the Slocan district held so many different varieties and grades of ores, smelting them was a difficult process,” explains the Sandon Historical Society. “As a result, many of these ores had to be transported to smelters at Trail, or even further afield in Washington state.”

The K&S line featured a total 33.4 miles (53.7 km) of track, with a three-mile (4.8 km) spur from Sandon to Cody. It began service on November 20, 1895. “From the terminus at Kaslo, the line gained altitude quickly by means of a switchback, then followed the Kaslo River past Fish and Bear lakes, climbing up the side of the mountain until it reached the site of Zincton. Old timers claimed that if the stumps got too large, the K&S line ran around them,” wrote Hearne and Wilkie in Canadian West magazine. “From there the going was really tough, and Payne Bluff, with its sheer drop of 1,080 feet, was rounded on a rocky ledge, with a ‘grasshopper’ trestle, just before reaching Sandon.”

Hoping to get in on the action, the Canadian Pacific Railway’s Nakusp & Slocan Railway was built from the Slocan Lake side, reaching Sandon within weeks of the K&S. Competition between the GNR and CPR was fierce. When the CPR built a station there on land claimed by the K&S its employees wasted no time in retaliating. A heavy cable was slung around the CPR depot and attached to a K&S locomotive, which then pulled it into Carpenter Creek. A newspaper report at the time stated that, “Oldtimers still recall with glee when the little line, with a stout cable and a snatch block, snaked into smithereens the brand new depot building of the big company…” While it lasted, the silver-lead boom in the Slocan kept both railways busy, doing double duty as freight and passenger lines. “The K&S was justifiably proud that it was able to offer service between Spokane, Washington and Sandon in less than 12 hours, a fact that made delicacies such as oysters a possibility in remote and rugged Sandon,” notes the Sandon Historical Society.

But as with all resource booms, the writing was on the wall for the end of an era. The CPR purchase of the Trail smelter, combined with increased American tariffs on ore imports and crashing commodity prices, steadily whittled down the profit margin. Added to these rising costs were those imposed by Nature – snowslides, avalanches and the annual spring washouts drove maintenance expenses sky-high. The devastating forest fire of 1910 finally bankrupted the K&S Railway. The GNR abandoned the line, prompting calls for the revoking of their charter and its accompanying land grant. Government negotiations resulted in the CPR agreeing to take on the K&S in February 1912, gradually converting the line to standard gauge. The final blow came in 1955 when torrential rains washed out a large section of track at Three Forks. Ore traffic had been dwindling for years and the CPR decided not to rebuild. Its right-of-way was used to build a new road to New Denver.

It was the sad end of one of the great engineering feats of the 19th century.